To Understand the Racist Nature of Blackface, One Has to Understand Its History

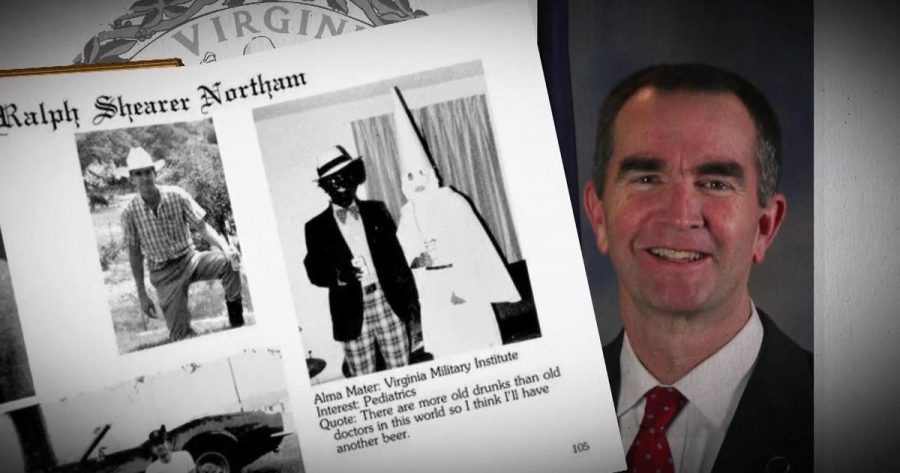

Virginia governor Ralph Northam (right) came under fire when his medical school yearbook page allegedly showing him in blackface became public.

February is Black History Month wherein America honors and remembers the countless African-Americans who proudly served our country and fought for the freedoms and equality that they now enjoy today. Despite these great strides in American progress, the legacy of these African-American individuals has been overshadowed by the abundance of racist beliefs and practices that still persist in modern society. Dozens of whites, including college fraternities and sororities, public officials and law enforcement officers, and even celebrities have been criticized for blackface incidents recently and over the years. So, what is blackface exactly? And why does it have such a negative stigma?

Blackface minstrelsy dates all the way back to 1830 in New York City, and it testifies to the exorbitant level of racism in American society both before and after the Civil War. Following the Civil War in the 1860s, it became one of the most popular forms of entertainment. Although there were minstrel forms created by African-American performers that trained black entertainers to dance, play traditional music, do comic routines to purposely act foolish, and place dark chalk on their faces to look even darker, most minstrel shows consisted entirely of white performers, disguised as blacks. White men would darken their faces to produce caricatures of black people, including large mouths, lips and eyes, wooly hair, and coal-black skin. They presented grotesque stereotypes of the slave culture of the American South, depicting black men and women as ridiculously ignorant, hypersexual, cowardly, superstitious, and lazy individuals, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

One of the most prominent blackface characters was known as “Jim Crow,” played by performer and playwright Thomas Dartmouth Rice. He wore a burnt-cork blackface mask and raggedy clothing, spoke in stereotypical black vernacular, and performed a caricatured song and dance routine called “Jump, Jim Crow” (or “Jumping Jim Crow”), which he said was inspired by a slave he saw. As a matter of fact, the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the South derived their name from this act.

These performances were intended to be funny to white audiences; however, to the black community these shows were both dehumanizing and demeaning. The influence of minstrel shows extended into the 20th century with the 1927 Hollywood release of The Jazz Singer, the first feature film with sound. One of the most popular singers of the twentieth century, Al Jolson, played a white minstrel performer who dressed in blackface in the movie. Classic American actors such as Shirley Temple, Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney also put on blackface in movies.

However, times have changed. In the 21st century, it is no longer acceptable to dress up in blackface or imitate a black person. Although in the past it was not considered a positive display of affection, people are much more sensitive to the issue today than they were decades ago. This is likely due the increased (though not complete) development of racial and ethnic diversity and acceptance in American society that was only taking its first baby steps in the 20th century (and still prevails today in a slighter form).

Various controversies have arisen in popular culture and politics regarding blackface recently. Some individuals find that the definition of blackface has been taken way out of proportions, applying to scenarios that it should not be related to. For example, last Halloween, a nurse at a Missouri hospital lost her job after using blackface to dress up as Beyoncé. Only a few days prior, Megyn Kelly on her NBC talk show “Megyn Kelly Today” had brought up the issue, citing the example of Luann de Lesseps, a member of the cast of the Bravo reality show “The Real Housewives of New York,” who came under fire earlier this year for dressing up as Diana Ross, complete with an over-sized Afro wig.

“But what is racist?” Kelly asked. “Because truly, you do get in trouble if you are a white person who puts on blackface on Halloween, or a black person who puts on whiteface for Halloween. Like, back when I was a kid, that was okay, as long as you were dressing up as, like, a character.”

Kelly later apologized for her comments, which had blown up all over social media as many responded to her ignorant question by pointing to the racist minstrel shows of the 1800s. As far as consequences go, she walked away from her show with $30 million, the remainder of her $69 million contract.

Malik Russell, a spokesman for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.), issued a statement in response: “Maybe in Megyn Kelly’s world, offensive acts and racism are O.K., but I assure you for individuals of color, blackface is always racist and never O.K.”

The latest major scandal to envelop the nation is one that threatens the political career of Democratic Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam. A racist photo found in his 1984 medical school yearbook has embroiled him into a bitter controversy over whether or not he should resign from office. The image reveals two people: one in blackface and one wearing a Ku Klux Klan hood and robe. Northam originally admitted that he was in the picture without saying which costume he was wearing, and apologized for his actions. But a day later, he denied he was in the photo, while also acknowledging he once put on blackface to imitate Michael Jackson at a dance contest in Texas decades ago, as reported by the Tampa Bay Times. If he resigns, Justin Fairfax, his lieutenant governor, will replace him, becoming the second African-American governor in Virginia history.

This is not the first and only time blackface has been infiltrated into current politics. In January, the Republican secretary of state in Florida, Michael Ertel, resigned after photos arose showing him dressed as a Hurricane Katrina victim in blackface at a party. Virginia’s Democratic attorney general Mark Herring also admitted that he wore blackface at a college party in 1980.

Blackface has even penetrated fashion when in February Gucci was targeted for racial insensitivity. According to People Magazine, the luxury brand introduced a new wool “Balaclava” sweater that featured a black turtleneck top that covered half the face and contained large red lips printed around a mouth cut-out. The $890 sweater released a wave of fury among many who believed that the design evoked blackface iconography. Gucci issued an apology, promising to further embed cultural diversity and awareness in their company.

It is apparent that the definition of blackface has transformed over time. Once meaning either a black or white person who put on dark makeup in a mocking performance of African slaves, the term has extended to individuals who make themselves appear black (even when trying to honorably reference historical figures and celebrities), while also applying to clothing such as the Gucci sweater, the Prada monkey figurine, or the Katy Perry shoes that appear to mimic the caricatures of African Americans that were once common-place and accepted in the nation’s embittered and turbulent past.